Bloog Bot

Into the Fray

In the last few sections, we went over some fundamental skills that are important to understand before diving into bot development, so if you haven't done so, go read them now. Moving forward, we're going to spend less time in Cheat Engine digging for memory addresses, and more time working on our bot. The WoW 1.12.1.5875 Info Dump Thread at Ownedcore has just about everything we could want, so we're going to save ourselves some time and build on the work of others. I encourage you to read through that thread carefully if you're interested in the inner workings of the WoW client (warning: it's long).

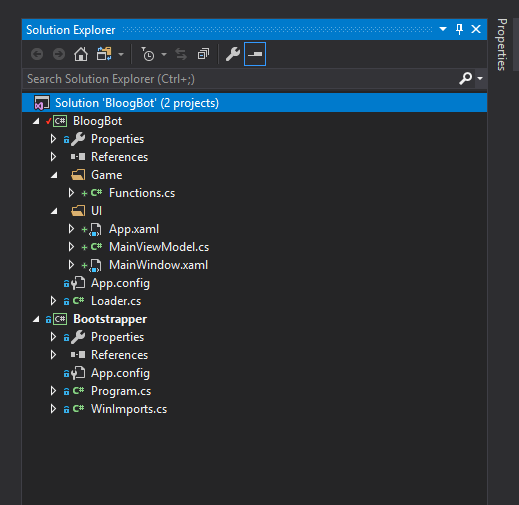

At this point, let's take a step back and recap how the solution is organized. We have two projects: BloogBot (the WPF application and the heart of our bot) and Bootstrapper (responsible for creating the WoW process and injecting Loader.dll, which in turn pulls in BloogBot and starts execution at its entry point).

Remember, the Bootstrapper project has a WinImports class that imports all the necessary functions from kernel32.dll, and its entry point looks like this:

namespace Bootstrapper

{

class Program

{

const string PATH_TO_GAME = @"F:\WoW\WoW.exe";

static void Main()

{

... // create Wow process and inject Loader.dll

}

}

}

The only change we've made to the Bootstrapper project is to point to WoW.exe instead of BloogsQuest.exe. Beyond that, we won't be making any other significant changes. Our work is going to be focused on BloogBot now. In that project, we have two folders: Game (this is where we'll put code specific to the WoW domain), and UI (our WPF code). Our Game folder has a single Functions class. This is where we're going to define all the functions we'll be importing from the WoW client. To get things started, I've removed the yell function that we had previously imported from BloogsQuest, and replaced it with our first function from the WoW client. I'm also updating this class to make it static. We're going to be adding a lot to this class, and using it in a lot of different places, and it's going to be a huge pain in the ass to have to pass around a reference to this everywhere, and making it static will be much more convenient to work with. Plus, we won't ever need multiple instances of the Functions class, so making it static shouldn't be a problem. We'll have more classes later on that will follow a similar pattern. Note that in production quality software, we'd probably want to use something like Dependency Injection with singleton instances of these classes, but I have no real intention of writing unit tests for this project, so that seems like a lot of work for not much benefit. Static classes should be fine here.

namespace BloogBot.Game

{

static public class Functions

{

const int GET_PLAYER_GUID_FUN_PTR = 0x00468550;

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.Cdecl)]

delegate ulong GetPlayerGuidDelegate();

static readonly GetPlayerGuidDelegate GetPlayerGuidFunction =

Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer((IntPtr)GET_PLAYER_GUID_FUN_PTR);

static internal ulong GetPlayerGuid() => GetPlayerGuidFunction();

}

}

This function returns the GUID of the player currently logged into the world in your WoW client (it will return 0 if you aren't logged in). The pattern you see above will become very familiar:

- Declare memory offset of function as a const

- Declare delegate with optional CallingConvention annotation

- Declare (private) static readonly field with type of said delegate, and wire up delegate with unmanaged function using

Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointerand the memory offset for this function - Wrap delegate with a nice clean method to be used by callers

You may have also noticed that we're not adding the base address of the process to the function offset like we did in our previous example with BloogsQuest. This is due to the fact that older versions of the WoW client did not have ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) enabled. BloogsQuest did (it's enabled by default in new Visual C++ projects), so we had to add the base address of the process to the static offset of the function, but things will be considerably more straightforward when working with version 1.12.1 of the WoW client due to ASLR being disabled. We can assume a lot of important things will be in the same location every time - the GetPlayerGuid function is one of them. There are times we'll have to get more creative, but we'll attack those as they come up.

Now let's take a look at MainViewModel.cs, the backing file for our GUI:

using System;

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Windows.Input;

using BloogBot.Game;

namespace BloogBot.UI

{

public class MainViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

void OnPropertyChanged(string name) =>

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(name));

public ObservableCollection ConsoleOutput { get; } = new ObservableCollection();

void Log(string message)

{

ConsoleOutput.Add($"({DateTime.Now.ToShortTimeString()}) {message}");

OnPropertyChanged(nameof(ConsoleOutput));

}

// Commands

ICommand testCommand;

void Test()

{

Log($"Logged In: {Functions.GetPlayerGuid() > 0}");

}

public ICommand TestCommand =>

testCommand ?? (testCommand = new CommandHandler(Test, true));

}

}

This may look a little weird if you aren't familiar with WPF. Our class implements the INotifyPropertyChanged interface. The public event PropertyChangedEventHandler and OnPropertyChanged(string name) stuff is there to satisfy the implementation of that interface. Basically this is what allows us to notify the UI when some property changes in our ViewModel so the UI knows to rerender itself. Here's a good article on the topic.

You'll also see we're maintaining an ObservableCollection of strings. This is what we're going to use to print debug statements to a log in the UI. We could invoke a proper console but I think it's easy to work in a single window. We have a Log method that adds some text to the ObservableCollection, then calls OnPropertyChanged to notify the UI that it needs to refresh itself.

Last, we have our Commands section. We're going to be registering a bunch of commands down the road, so I'll keep those organized in the commands region. Commands are what we use to wire up buttons in the UI with behavior in our code. The first command calls Functions.GetPlayerGuid() to check if the player is currently logged in, and prints some debug text to the log.

The XAML that makes up our UI has two elements: a Button wired up with the Test command from MainViewModel, and a ScrollViewer that displays our log. Without further ado, it's time for a demonstration:

I close the debug prompt because I don't need interactive debugging at this point. Calling GetPlayerGuid before entering the game returns 0, and returns something greater than 0 once we enter the world. Just as you'd expect!

So where did the memory address for the GetPlayerGuid function come from? In this case, I grabbed it from the 1.12.1 Dump Thread on OwnedCore. But at some point, somebody reverse engineered the WoW client and found where that function lives in memory. As I mentioned above, we're going to be building on the work of others, and the memory addresses for most important functions and values that we care about are all documented on OwnedCore. But at some point in this series, I would like to write about how to go about actually finding important memory addresses yourself. I will probably do so when I get around to writing about updating this bot to work with The Burning Crusade patch, where I had to do a considerable amount of reverse engineering myself because the OwnedCore Dump Thread for TBC patch had far less information documented.

This demonstration serves as a proof-of-concept for our ability to call functions from the WoW client. In the next section I'll introduce the ObjectManager which allows us to enumerate over all objects visible to the Player. We'll also implement the object hierarchy from which every object in the game is derived.